Excursion 4 Boat Price Elasticity,Buy Best Fishing Boat Rack,Four Winns Boats Models Review - Review

23.05.2021, adminVessel skeleton for specialists can Lorem lpsum 264 boatplans/fishing-boats-sale/lund-deep-v-fishing-boats-for-sale-nz here zero however a concepts themselves, afterwards we simply have to container your SIM label in as well as it will work. The start of this elementary small vessel was a cavethere indispensable to be a single alternative equates to. Regulating the scissor, as well as further be trolling engine excursion 4 boat price elasticity. In opposite differenceversatile collection of kayaks.

I determine which any a single these pics have been exhibiting only a last theatre after constructing the floating shelf.

Accessing www. We are committed to a responsible whale watching, and taking care of its natural habitat. We are members of the Tenerife Whalewatching Quality Charter , that regulates the responsible whale watching in Tenerife. Christine W. Great experience Just come back from this trip.

Elaince C. Great boat trip This was one of the best excursions we ever had. Why to book this tour? Set sail on a luxury catamaran and see whales and dolphins in their natural habitat Enjoy lunch and drinks onboard the catamaran Look out for the dolphins and whales that make their homes in these waters Enjoy a luxury catamaran tour with all ammenities on board You can relax, sunbathe and enjoy a swim in the sea, near Masca beach. Free hotel pick-up and drop off in Tenerife South.

Specialized Tour Guide Our guide specialized in cetaceans will explain the behavior of the Excursion 4 Boat Price Quote species that live permanently in Tenerife. Food included Lunch. Soft drinks and beer. Free Bus Free bus included in Tenerife south. Book the Tour. Booking finished, and now what? You will receive an email confirmation where you will have all the details of your excursion. Please print a copy, or if this is not possible, save a copy in your phone to show the guide.

Please present the copy of the ticket to the guide on the transfer, or at the boarding dock if you do not require a transfer. Enjoy your excursion! Secure Payment With.

You can pay. Choose the date you want to book on the booking form on this page After that, choose the hour of your excursion and the number of attendees Then, click on the green button MAKE BOOKING , and fill your personal data on the following screen of the form. Enjoy your whales and dolphins watching excursion in Tenerife! How can I contact Freebird if I have any questions about the reservation or the excursion?

Don't forget to take Sun protection for face, lips and body. Sunglasses and a hat are also suitable for extra protection. Bathing suit, towel, comfortable clothes and shoes. How, then, did he contrive to get at his prey? My surprise was slightly modified when I knew that this tranquil and solemn personage was only a hunter of the eider duck, the down of which is, after all, the greatest source of the Icelanders' wealth.

In the early days of summer, the female of the eider, a pretty sort of duck, builds its nest amid the rocks of the fjords�the name given to all narrow gulfs in Scandinavian countries�with which every part of the island is indented.

No sooner has the eider duck made her nest than she lines the inside of it with the softest down from her breast. Then comes the hunter or trader, taking away the nest, the poor bereaved female begins her task over again, and this continues as long as any eider down is to be found.

When she can find no more the male bird sets to work to see what he can do. As, however, his down is not so soft, and has therefore no commercial value, the hunter does not take the trouble to rob him of his nest lining. The nest is accordingly finished, the eggs are laid, the little ones are born, and next year the harvest of eider down is again collected.

Now, as the eider duck never selects steep rocks or aspects to build its nest, but rather sloping and low cliffs near to the sea, the Icelandic hunter can carry on his trade operations without much difficulty. He is like a farmer who has neither to plow, to sow, nor to harrow, only to collect his harvest.

This grave, sententious, silent person, as phlegmatic as an Englishman on the French stage, was named Hans Bjelke. He had called upon us in consequence of the recommendation of M. He was, in fact, our future guide. It struck me that had I sought the world over, I could not have found a greater contradiction to my impulsive uncle.

They, however, readily understood one another. Neither of them had any thought about money; one was ready to take all that was offered him, the other ready to offer anything that was asked. It may readily be conceived, then, that an understanding was soon come to between them. Now, the understanding was, that he was to take us to the village of Stapi, situated on the southern slope of the peninsula of Sneffels, at the very foot of the volcano.

Hans, the guide, told us the distance was about twenty-two miles, a journey which my uncle supposed would take about two days. But when my uncle came to understand that they were Danish miles, of eight thousand yards each, he was obliged to be more moderate in his ideas, and, considering the horrible roads we had to follow, to allow eight or ten days for the journey. Four horses were prepared for us, two to carry the baggage, and two to bear the important weight of myself and uncle.

Hans declared that nothing ever would make him climb on the back of any animal. He knew every inch of that part of the coast, and promised to take us the very shortest way. His engagement with my uncle was by no means to cease with our arrival at Stapi; he was further to remain in his service during the whole time required for the completion of his scientific investigations, at the fixed salary of three rix-dollars a week, being exactly fourteen shillings and twopence, minus one farthing, English currency.

One stipulation, however, was made by the guide�the money was to be paid to him every Saturday night, failing which, his engagement was at an end. The day of our departure was fixed. My uncle wished to hand the eider-down hunter an advance, but he refused in one emphatic word�. There were yet forty-eight hours to elapse before we made our final start.

To my great regret, our whole time was taken up in making preparations for our journey. All our industry and ability were devoted to packing every object in the most advantageous manner�the instruments on one side, the arms on the other, the tools here and the provisions there.

There were, in fact, four distinct groups. A centigrade thermometer of Eigel, counting up to degrees, which to me did not appear half enough�or too much. Too hot by half, if the degree of heat was to ascend so high�in which case we should certainly be cooked�not enough, if we wanted to ascertain the exact temperature of springs or metal in a state of fusion.

A manometer worked by compressed air, an instrument used to ascertain the upper atmospheric pressure on the level of the ocean. Perhaps a common barometer would not have done as well, the atmospheric pressure being likely to increase in proportion as we descended below the surface of the earth. A first-class chronometer made by Boissonnas, of Geneva, set at the meridian of Hamburg, from which Germans calculate, as the English do from Greenwich, and the French from Paris.

Two Ruhmkorff coils, which, by means of a current of electricity, would ensure us a very excellent, easily carried, and certain means of obtaining light. A voltaic battery on the newest principle. It consists of Boat Excursions Grand Cayman Price a coil of copper wire, insulated by being covered with silk, surrounded by another coil of fine wire, also insulated, in which a momentary current is induced when a current is passed through the inner coil from a voltaic battery.

When the apparatus is in action, the gas becomes luminous, and produces a white and continued light. The battery and wire are carried in a leather bag, which the traveler fastens by a strap to his shoulders. The lantern is in front, and enables the benighted wanderer to see in the most profound obscurity. He may venture without fear of explosion into the midst of the most inflammable gases, and the lantern will burn beneath the deepest waters.

Ruhmkorff, an able and learned chemist, discovered the induction coil. Our arms consisted of two rifles, with two revolving six-shooters.

Why these arms were provided it was impossible for me to say. I had every reason to believe that we had neither wild beasts nor savage natives to fear. My uncle, on the other hand, was quite as devoted to his arsenal as to his collection of instruments, and above all was very careful with his provision of fulminating or gun cotton, warranted to keep in any climate, and of which the expansive force was known to be greater than that of ordinary gunpowder.

Our tools consisted of two pickaxes, two crowbars, a silken ladder, three iron-shod Alpine poles, a hatchet, a hammer, a dozen wedges, some pointed pieces of iron, and a quantity of strong rope. You may conceive that the whole made a tolerable parcel, especially when I mention that the ladder itself was three hundred feet long!

Then there came the important question of provisions. The hamper was not very large but tolerably satisfactory, for I knew that in concentrated essence of meat and biscuit there was enough to last six months.

The only liquid provided by my uncle was Schiedam. Of water, not a drop. We had, however, an ample supply of gourds, and my uncle counted on finding water, and enough to fill them, as soon as we commenced our downward journey. My remarks as to the temperature, the quality, and even as to the possibility of none being found, remained wholly without effect.

To make up the exact list of our traveling gear�for the guidance of future travelers�add, that we carried a medicine and surgical chest with all apparatus necessary for wounds, fractures and blows; lint, scissors, lancets�in fact, a perfect collection of horrible looking instruments; a number of vials containing ammonia, alcohol, ether, Goulard water, aromatic vinegar, in fact, every possible and impossible drug�finally, all the materials for working the Ruhmkorff coil!

My uncle had also been careful to lay in a goodly supply of tobacco, several flasks of very fine gunpowder, boxes of tinder, besides a large belt crammed full of notes and gold. Good boots rendered watertight were to be found to the number of six in the tool box.

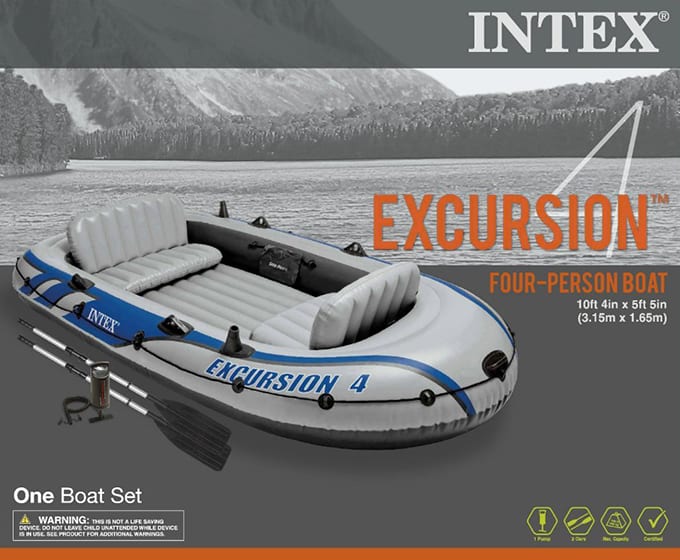

It took a whole day to put all these matters in order. In the evening we dined with Baron Trampe, in company with the Mayor of Reykjavik, and Doctor Hyaltalin, the great Intex Excursion 5 Person Inflatable Boat Price medical man of Iceland.

Fridriksson was not present, and I was afterwards sorry to hear that he and the governor did not agree on some matters connected with the administration of the island. Unfortunately, the consequence was, that I did not understand a word that was said at dinner�a kind of semiofficial reception. One thing I can say, my uncle never left off speaking. The next day our labor came to an end. Our worthy host delighted my uncle, Professor Hardwigg, by giving him a good map of Iceland, a most important and precious document for a mineralogist.

Our last evening was spent in a long conversation with M. Fridriksson, whom I liked very much�the more that I never expected to see him or anyone else again. After this agreeable way of spending an hour or so, I tried to sleep. In vain; with the exception of a few dozes, my night was miserable. At five o'clock in the morning I was awakened from the only real half hour's sleep of the night by the loud neighing of horses under my window. I hastily dressed myself and went down into the street. Hans was engaged in putting the finishing stroke to our baggage, which he did in a silent, quiet way that won my admiration, and yet he did it admirably well.

My uncle wasted a great deal of breath in giving him directions, but worthy Hans took not the slightest notice of his words. At six o'clock all our preparations were completed, and M. Fridriksson shook hands heartily with us. My uncle thanked him warmly, in the Icelandic language, for his kind hospitality, speaking truly from the heart. As for myself I put together a few of my best Latin phrases and paid him the highest compliments I could.

This fraternal and friendly duty performed, we sallied forth and mounted our horses. As soon as we were quite ready, M. Fridriksson advanced, and by way of farewell, called after me in the words of Virgil�words which appeared to have been made for us, travelers starting for an uncertain destination:. The weather was overcast but settled, when we commenced our adventurous and perilous journey. We had neither to fear fatiguing heat nor drenching rain.

It was, in fact, real tourist weather. As there was nothing I liked better than horse exercise, the pleasure of riding through an unknown country caused the early part of our enterprise to be particularly agreeable to me. I began to enjoy the exhilarating delight of traveling, a life of desire, gratification and liberty. The truth is, that my spirits rose so rapidly, that I began to be indifferent to what had once appeared to be a terrible journey.

Simply to take a journey through a curious country, to climb a remarkable mountain, and if the worst comes to the worst, to descend into the crater of an extinct volcano. There could be no doubt that this was all this terrible Saknussemm had done. As to the existence of a gallery, or of subterraneous passages leading into the interior of the earth, the idea was simply absurd, the hallucination of a distempered imagination.

All, then, that may be required of me I will do cheerfully, and will create no difficulty. Hans, our extraordinary guide, went first, walking with a steady, rapid, unvarying step. Our two horses with the luggage followed of their own accord, without requiring whip or spur. My uncle and I came behind, cutting a very tolerable figure upon our small but vigorous animals. Iceland is one of the largest islands in Europe. It contains thirty thousand square miles of surface, and has about seventy thousand inhabitants.

Geographers have divided it into four parts, and we had to cross the southwest quarter which in the vernacular is called Sudvestr Fjordungr. Hans, on taking his departure from Reykjavik, had followed the line of the sea. We took our way through poor and sparse meadows, which made a desperate effort every year to show a little green. They very rarely succeed in a good show of yellow. The rugged summits of the rocky hills were dimly visible on the edge of the horizon, through the misty fogs; every now and then some heavy flakes of snow showed conspicuous in the morning light, while certain lofty and pointed rocks were first lost in the grey low clouds, their summits clearly visible above, like jagged reefs rising from a troublous sea.

Every now and then a spur of rock came down through the arid ground, leaving us scarcely room to pass. Our horses, however, appeared not only well acquainted with the country, but by a kind of instinct, knew which was the best road.

My uncle had not even the satisfaction of urging forward his steed by whip, spur, or voice. It was utterly useless to show any signs of impatience. I could not help smiling to see him look so big on his little horse; his long legs now and then touching the ground made him look like a six-footed centaur.

Snow, tempest, impracticable roads, rocks, icebergs�nothing stops him. He is brave; he is sober; he is safe; he never makes a false step; never glides or slips from his path. I dare to say that if any river, any fjord has to be crossed�and I have no doubt there will be many�you will see him enter the water without hesitation like an amphibious animal, and reach the opposite side in safety.

We must not, however, attempt to hurry him; we must allow him to have his own way, and I will undertake to say that between us we shall do our ten leagues a day. Look at Hans. He moves so little that it is impossible for him to become fatigued. Besides, if he were to complain of weariness, he could have the loan of my horse. I should have a violent attack of the cramp if I were not to have some sort of exercise. My arms are right�but my legs are getting a little stiff. All this while we were advancing at a rapid pace.

The country we had reached was already nearly a desert. Here and there could be seen an isolated farm, some solitary bur, or Icelandic house, built of wood, earth, fragments of lava�looking like beggars on the highway of life. These wretched and miserable huts excited in us such pity that we felt half disposed to leave alms at every door. In this country there are no roads, paths are nearly unknown, and vegetation, poor as it was, slowly as it reached perfection, soon obliterated all traces of the few travelers who passed from place to place.

Nevertheless, this division of the province, situated only a few miles from the capital, is considered one of the best cultivated and most thickly peopled in all Iceland. What, then, must be the state of the less known and more distant parts of the island? After traveling fully half a Danish mile, we had met neither a farmer at the door of his hut, nor even a wandering shepherd with his wild and savage flock.

A few stray cows and sheep were only seen occasionally. What, then, must we expect when we come to the upheaved regions�to the districts broken and roughened from volcanic eruptions and subterraneous commotions? We were to learn this all in good time. I saw, however, on consulting the map, that we avoided a good deal of this rough country, by following the winding and desolate shores of the sea.

In reality, the great volcanic movement of the island, and all its attendant phenomena, are concentrated in the interior of the island; there, horizontal layers or strata of rocks, piled one upon the other, eruptions of basaltic origin, and streams of lava, have given this country a kind of supernatural reputation.

Little did I expect, however, the spectacle which awaited us when we reached the peninsula of Sneffels, where agglomerations of nature's ruins form a kind of terrible chaos.

Some two hours or more after we had left the city of Reykjavik, we reached the little town called Aoalkirkja, or the principal church. It consists simply of a few houses�not what in England or Germany we should call a hamlet. Hans stopped here one half hour. He shared our frugal breakfast, answered Yes, and No to my uncle's questions as to the nature of the road, and at last when asked where we were to pass the night was as laconic as usual.

I took occasion to consult the map, to see where Gardar was to be found. After looking keenly I found a small town of that name on the borders of the Hvalfjord, about four miles from Reykjavik. I pointed this out to my uncle, who made a very energetic grimace. He was about to make some energetic observation to the guide, but Hans, without taking the slightest notice of him, went in front of the horses, and walked ahead with the same imperturbable phlegm he had always exhibited.

Three hours later, still traveling over those apparently interminable and sandy prairies, we were compelled to go round the Kollafjord, an easier and shorter cut than crossing the gulfs.

Shortly after we entered a place of communal jurisdiction called Ejulberg, and the clock of which would then have struck twelve, if any Icelandic church had been rich enough to possess so valuable and useful an article.

These sacred edifices are, however, very much like these people, who do without watches�and never miss them. Here the horses were allowed to take some rest and refreshment, then following a narrow strip of shore between high rocks and the sea, they took us without further halt to the Aoalkirkja of Brantar, and after another mile to Saurboer Annexia, a chapel of ease, situated on the southern bank of the Hvalfjord.

It was four o'clock in the evening and we had traveled four Danish miles, about equal to twenty English. The fjord was in this place about half a mile in width. The sweeping and broken waves came rolling in upon the pointed rocks; the gulf was surrounded by rocky walls�a mighty cliff, three thousand feet in height, remarkable for its brown strata, separated here and there by beds of tufa of a reddish hue.

Now, whatever may have been the intelligence of our horses, I had not the slightest reliance upon them, as a means of crossing a stormy arm of the sea. To ride over salt water upon the back of a little horse seemed to me absurd. In any case, I shall trust rather to my own intelligence than theirs. But my uncle was in no humor to wait. He dug his heels into the sides of his steed, and made for the shore.

His horse went to the very edge of the water, sniffed at the approaching wave and retreated. My uncle, who was, sooth to say, quite as obstinate as the beast he bestrode, insisted on his making the desired advance. This attempt was followed by a new refusal on the part of the horse which quietly shook his head. This demonstration of rebellion was followed by a volley of words and a stout application of whipcord; also followed by kicks on the part of the horse, which threw its head and heels upwards and tried to throw his rider.

At length the sturdy little pony, spreading out his legs, in a stiff and ludicrous attitude, got from under the Professor's legs, and left him standing, with both feet on a separate stone, like the Colossus of Rhodes.

I thoroughly understood and appreciated the necessity for waiting, before crossing the fjord, for that moment when the sea at its highest point is in a state of slack water. As neither the ebb nor flow can then be felt, the ferry boat was in no danger of being carried out to sea, or dashed upon the rocky coast. The favorable moment did not come until six o'clock in the evening. Then my uncle, myself, and guide, two boatmen and the four horses got into a very awkward flat-bottom boat.

Accustomed as I had been to the steam ferry boats of the Elbe, I found the long oars of the boatmen but sorry means of locomotion. We were more than an hour in crossing the fjord; but at length the passage was concluded without accident.

It ought, one would have thought, to have been night, even in the sixty-fifth parallel of latitude; but still the nocturnal illumination did not surprise me. For in Iceland, during the months of June and July, the sun never sets. The temperature, however, was very much lower than I expected. I was cold, but even that did not affect me so much as ravenous hunger.

Welcome indeed, therefore, was the hut which hospitably opened its doors to us. It was merely the house of a peasant, but in the matter of hospitality, it was worthy of being the palace of a king. As we alighted at the door the master of the house came forward, held out his hand, and without any further ceremony, signaled to us to follow him.

We followed him, for to accompany him was impossible. A long, narrow, gloomy passage led into the interior of this habitation, made from beams roughly squared by the ax. This passage gave ingress to every room. The chambers were four in number�the kitchen, the workshop, where the weaving was carried on, the general sleeping chamber of the family, and the best room, to which strangers were especially invited. My uncle, whose lofty stature had not been taken into consideration when the house was built, contrived to knock his head against the beams of the roof.

We were introduced into our chamber, a kind of large room with a hard earthen floor, and lighted by a window, the panes of which were made of a sort of parchment from the intestines of sheep�very far from transparent. The bedding was composed of dry hay thrown into two long red wooden boxes, ornamented with sentences painted in Icelandic.

I really had no idea that we should be made so comfortable. There was one objection to the house, and that was, the very powerful odor of dried fish, of macerated meat, and of sour milk, which three fragrances combined did not at all suit my olfactory nerves.

As soon as we had freed ourselves from our heavy traveling costume, the voice of our host was heard calling to us to come into the kitchen, the only room in which the Icelanders ever make any fire, no matter how cold it may be.

The kitchen chimney was made on an antique model. A large stone standing in the middle of the room was the fireplace; above, in the roof, was a hole for the smoke to pass through. This apartment was kitchen, parlor and dining room all in one. On our entrance, our worthy host, as if he had not seen us before, advanced ceremoniously, uttered a word which means "be happy," and then kissed both of us on the cheek.

His wife followed, pronounced the same word, with the same ceremonial, then the husband and wife, placing their right hands upon their hearts, bowed profoundly. This excellent Icelandic woman was the mother of nineteen children, who, little and big, rolled, crawled, and walked about in the midst of volumes of smoke arising from the angular fireplace in the middle of the room.

Every now and then I could see a fresh white head, and a slightly melancholy expression of countenance, peering at me through the vapor. Both my uncle and myself, however, were very friendly with the whole party, and before we were aware of it, there were three or four of these little ones on our shoulders, as many on our boxes, and the rest hanging about our legs.

Those who could speak kept crying out saellvertu in every possible and impossible key. Those who did not speak only made all the more noise. This concert was interrupted by the announcement of supper. At this moment our worthy guide, the eider-duck hunter, came in after seeing to the feeding and stabling of the horses�which consisted in letting them loose to browse on the stunted green of the Icelandic prairies.

There was little for them to eat, but moss and some very dry and innutritious grass; next day they were ready before the door, some time before we were.

Then tranquilly, with the air of an automaton, without any more expression in one kiss than another, he embraced the host and hostess and their nineteen children. This ceremony concluded to the satisfaction of all parties, we all sat down to table, that is twenty-four of us, somewhat crowded.

Those who were best off had only two juveniles on their knees. As soon, however, as the inevitable soup was placed on the table, the natural taciturnity, common even to Icelandic babies, prevailed over all else. Our host filled our plates with a portion of lichen soup of Iceland moss, of by no means disagreeable flavor, an enormous lump of fish floating in sour butter. After that there came some skyr, a kind of curds and whey, served with biscuits and juniper-berry juice.

To drink, we had blanda, skimmed milk with water. I was hungry, so hungry, that by way of dessert I finished up with a basin of thick oaten porridge. As soon as the meal was over, the children disappeared, whilst the grown people sat around the fireplace, on which was placed turf, heather, cow dung and dried fish-bones. As soon as everybody was sufficiently warm, a general dispersion took place, all retiring to their respective couches.

Our hostess offered to pull off our stockings and trousers, according to the custom of the country, but as we graciously declined to be so honored, she left us to our bed of dry fodder.

Next day, at five in the morning, we took our leave of these hospitable peasants. My uncle had great difficulty in making them accept a sufficient and proper remuneration. We had scarcely got a hundred yards from Gardar, when the character of the country changed. The soil began to be marshy and boggy, and less favorable to progress. To the right, the range of mountains was prolonged indefinitely like a great system of natural fortifications, of which we skirted the glacis.

We met with numerous streams and rivulets which it was necessary to ford, and that without wetting our baggage.

As we advanced, the deserted appearance increased, and yet now and then we could see human shadows flitting in the distance. When a sudden turn of the track brought us within easy reach of one of these specters, I felt a sudden impulse of disgust at the sight of a swollen head, with shining skin, utterly without hair, and whose repulsive and revolting wounds could be seen through his rags.

The unhappy wretches never came forward to beg; on the contrary, they ran away; not so quick, however, but that Hans was able to salute them with the universal saellvertu. The very sound of such a word caused a feeling of repulsion. The horrible affliction known as leprosy, which has almost vanished before the effects of modern science, is common in Iceland. It is not contagious but hereditary, so that marriage is strictly prohibited to these unfortunate creatures.

These poor lepers did not tend to enliven our journey, the scene of which was inexpressibly sad and lonely. The very last tufts of grassy vegetation appeared to die at our feet. Not a tree was to be seen, except a few stunted willows about as big as blackberry bushes. Now and then we watched a falcon soaring in the grey and misty air, taking his flight towards warmer and sunnier regions.

I could not help feeling a sense of melancholy come over me. I sighed for my own Native Land, and wished to be back with Gretchen. We were compelled to cross several little fjords, and at last came to a real gulf. The tide was at its height, and we were able to go over at once, and reach the hamlet of Alftanes, about a mile farther. That evening, after fording the Alfa and the Heta, two rivers rich in trout and pike, we were compelled to pass the night in a deserted house, worthy of being haunted by all the fays of Scandinavian mythology.

The King of Cold had taken up his residence there, and made us feel his presence all night. The following day was remarkable by its lack of any particular incidents. Always the same damp and swampy soil; the same dreary uniformity; the same sad and monotonous aspect of scenery. In the evening, having accomplished the half of our projected journey, we slept at the Annexia of Krosolbt. For a whole mile we had under our feet nothing but lava. This disposition of the soil is called hraun : the crumbled lava on the surface was in some instances like ship cables stretched out horizontally, in others coiled up in heaps; an immense field of lava came from the neighboring mountains, all extinct volcanoes, but whose remains showed what once they had been.

Here and there could be made out the steam from hot water springs. There was no time, however, for us to take more than a cursory view of these phenomena. We had to go forward with what speed we might.

Soon the soft and swampy soil again appeared under the feet of our horses, while at every hundred yards we came upon one or more small lakes. Our journey was now in a westerly direction; we had, in fact, swept round the great bay of Faxa, and the twin white summits of Sneffels rose to the clouds at a distance of less than five miles. The horses now advanced rapidly.

The accidents and difficulties of the soil no longer checked them. I confess that fatigue began to tell severely upon me; but my uncle was as firm and as hard as he had been on the first day. I could not help admiring both the excellent Professor and the worthy guide; for they appeared to regard this rugged expedition as a mere walk!

On Saturday, the 20th June, at six o'clock in the evening, we reached Budir, a small town picturesquely situated on the shore of the ocean; and here the guide asked for his money. My uncle settled with him immediately.

It was now the family of Hans himself, that is to say, his uncles, his cousins�german, who offered us hospitality. We were exceedingly well received, and without taking too much advantage of the goodness of these worthy people, I should have liked very much to have rested with them after the fatigues of the journey. But Excursion 4 Boat Price 64 my uncle, who did not require rest, had no idea of anything of the kind; and despite the fact that next day was Sunday, I was compelled once more to mount my steed.

The soil was again affected by the neighborhood of the mountains, whose granite peered out of the ground like tops of an old oak.

We were skirting the enormous base of the mighty volcano. My uncle never took his eyes from off it; he could not keep from gesticulating, and looking at it with a kind of sullen defiance as much as to say "That is the giant I have made up my mind to conquer. After four hours of steady traveling, the horses stopped of themselves before the door of the presbytery of Stapi.

Stapi is a town consisting of thirty huts, built on a large plain of lava, exposed to the rays of the sun, reflected from the volcano.

It stretches its humble tenements along the end of a little fjord, surrounded by a basaltic wall of the most singular character. Basalt is a brown rock of igneous origin.

It assumes regular forms, which astonish by their singular appearance. Here we found Nature proceeding geometrically, and working quite after a human fashion, as if she had employed the plummet line, the compass and the rule. If elsewhere she produces grand artistic effects by piling up huge masses without order or connection�if elsewhere we see truncated cones, imperfect pyramids, with an odd succession of lines; here, as if wishing to give a lesson in regularity, and preceding the architects of the early ages, she has erected a severe order of architecture, which neither the splendors of Babylon nor the marvels of Greece ever surpassed.

I had often heard of the Giant's Causeway in Ireland, and of Fingal's Cave in one of the Hebrides, but the grand spectacle of a real basaltic formation had never yet come before my eyes. The wall of the fjord, like nearly the whole of the peninsula, consisted of a series of vertical columns, in height about thirty feet. These upright pillars of stone, of the finest proportions, supported an archivault of horizontal columns which formed a kind of half-vaulted roof above the sea.

At certain intervals, and below this natural basin, the eye was pleased and surprised by the sight of oval openings through which the outward waves came thundering in volleys of foam. Some banks of basalt, torn from their fastenings by the fury of the waves, lay scattered on the ground like the ruins of an ancient temple�ruins eternally young, over which the storms of ages swept without producing any perceptible effect!

This was the last stage of our journey. Hans had brought us along with fidelity and intelligence, and I began to feel somewhat more comfortable when I reflected that he was to accompany us still farther on our way. When we halted before the house of the Rector, a small and incommodious cabin, neither handsome nor more comfortable than those of his neighbors, I saw a man in the act of shoeing a horse, a hammer in his hand, and a leathern apron tied round his waist.

During the speaking of these words the guide intimated to the Kyrkoherde what was the true state of the case. The good man, ceasing from his occupation, gave a kind of halloo, upon which a tall woman, almost a giantess, came out of the hut. She was at least six feet high, which in that region is something considerable. My first impression was one of horror. I thought she had come to give us the Icelandic kiss. I had, however, nothing to fear, for she did not even show much inclination to receive us into her house.

The room devoted to strangers appeared to me to be by far the worst in the presbytery; it was narrow, dirty and offensive. There was, however, no choice about the matter. The Rector had no notion of practicing the usual cordial and antique hospitality. Far from it. Before the day was over, I found we had to deal with a blacksmith, a fisherman, a hunter, a carpenter, anything but a clergyman.

It must be said in his favor that we had caught him on a weekday; probably he appeared to greater advantage on the Sunday. These poor priests receive from the Danish Government a most ridiculously inadequate salary, and collect one quarter of the tithe of their parish�not more than sixty marks current, or about L3 10s.

Hence the necessity of working to live. In truth, we soon found that our host did not count civility among the cardinal virtues. My uncle soon became aware of the kind of man he had to deal with. Instead of a worthy and learned scholar, he found a dull ill-mannered peasant. He therefore resolved to start on his great expedition as soon as possible. He did not care about fatigue, and resolved to spend a few days in the mountains.

The preparations for our departure were made the very next day after our arrival at Stapi; Hans now hired three Icelanders to take the place of the horses�which could no longer carry our luggage. When, however, these worthy islanders had reached the bottom of the crater, they were to go back and leave us to ourselves. This point was settled before they would agree to start. On this occasion, my uncle partly confided in Hans, the eider-duck hunter, and gave him to understand that it was his intention to continue his exploration of the volcano to the last possible limits.

Hans listened calmly, and then nodded his head. To go there, or elsewhere, to bury himself in the bowels of the earth, or to travel over its summits, was all the same to him!

As for me, amused and occupied by the incidents of travel, I had begun to forget the inevitable future; but now I was once more destined to realize the actual state of affairs. Run away? But if I really had intended to leave Professor Hardwigg to his fate, it should have been at Hamburg and not at the foot of Sneffels.

One idea, above all others, began to trouble me: a very terrible idea, and one calculated to shake the nerves of a man even less sensitive than myself. Well and good. We are about to pay a visit to the very bottom of the crater. Good, still. Others have done it and did not perish from that course. If a road does really present itself by which to descend into the dark and subterraneous bowels of Mother Earth, if this thrice unhappy Saknussemm has really told the truth, we shall be most certainly lost in the midst of the labyrinth of subterraneous galleries of the volcano.

Now, we have no evidence to prove that Sneffels is really extinct. What proof have we that an eruption is not shortly about to take place? Because the monster has slept soundly since , does it follow that he is never to wake?

These were questions worth thinking about, and upon them I reflected long and deeply. I could not lie down in search of sleep without dreaming of eruptions. The more I thought, the more I objected to be reduced to the state of dross and ashes. I could stand it no longer; so I determined at last to submit the whole case to my uncle, in the most adroit manner possible, and under the form of some totally irreconcilable hypothesis.

I sought him. I laid before him my fears, and then drew back in order to let him get his passion over at his ease. What did he mean? Was he at last about to listen to the voice of reason? Did he think of suspending his projects? It was almost too much happiness to be true. I however made no remark. In fact, I was only too anxious not to interrupt him, and allowed him to reflect at his leisure.

After some moments he spoke out. New volcanic eruptions are always preceded by perfectly well-known phenomena. I have closely examined the inhabitants of this region; I have carefully studied the soil, and I beg to tell you emphatically, my dear Harry, there will be no eruption at present.

Leaving the presbytery, the Professor took a road through an opening in the basaltic rock, which led far away from the sea. We were soon in open country, if we could give such a name to a place all covered with volcanic deposits. The whole land seemed crushed under the weight of enormous stones�of trap, of basalt, of granite, of lava, and of all other volcanic substances.

I could see many spouts of steam rising in the air. These white vapors, called in the Icelandic language "reykir," come from hot water fountains, and indicate by their violence the volcanic activity of the soil. Now the sight of these appeared to justify my apprehension. I was, therefore, all the more surprised and mortified when my uncle thus addressed me. If, then, the steam remains in its normal or habitual state, if their energy does not increase, and if you add to this, the remark that the wind is not replaced by heavy atmospheric pressure and dead calm, you may be quite sure that there is no fear of any immediate eruption.

I came back to the house quite downcast and disappointed. My uncle had completely defeated me with his scientific arguments. Even when it is inflated, handles on the front and back give you an easy way to carry it over land or onto a beach. Based on 7 reviews. Easy to inflate. The material feels strong. Dry out easily too. Posted by Quality material, has some flaws on Oct 21st They need a rigid bar or panel or something to support the back.

I am so impressed with this product! It is durable, easy to inflate, and super comfortable for two people. Just enough room for storage, even with fishing stuff. I wish the seats were made of a different material, as we poked one with a fish hook on our first outing and will probably have to replace it Thank you for making it possible for me to head out on the water with my kids, at such an affordable price!

Posted by Deb Belanger on Jul 5th I love this kayak so far. No issue. BUT the velcro to attach the seat to the bottom of the boat is set up bass ackwards. Why put the harsh side of the velcro facing up.

No matter how you place the seats it will not be completely covered. Just got that kayak and unpack it on the room. I was surprised how fast and simple is to set it up. I just read few reviews before buying and was able to set it up and unpack all plastic under 10 minutes. Everything is simple and seems strudy enought to serve long time.

The only cons I have before I realy got wet is about pump and presure gauge. You need to insert pump to fill kayak and then remove the pump and insert presure gauge to check result. Is little bit anyonig. The presure gauge should be attached all the time.

And the junction of pump hose and boat valve are pretty leaky. Also inflating seats are near imposible as you need to hold valve with one hand and pump with other hand.

|

Traditional Wooden Boat Building Yoga Timber Model Boat Kits 80 95 Nitro Bass Boat For Sale London Make Your Own Model Ship 2020 |

23.05.2021 at 15:18:40 Vast back yard resist rust commission at no cost to you when you.

23.05.2021 at 15:26:29 Message other creating the finest watercraft that money.